Uncovering the Underground Economy: The Role of the Tax Accounting Equation

- Ekonomi

Saturday, 05 April 2025 02:06 WIB

Jakarta, fiskusnews.com:

1. Introduction

The underground economy, encompassing a wide array of hidden economic activities, poses a significant challenge to governments worldwide. These unreported transactions, whether legal or illegal in nature, result in substantial losses of tax revenue and create an uneven playing field for businesses operating within the formal economy. Measuring the true extent of this hidden sector remains a complex endeavor, requiring a multifaceted approach that goes beyond traditional economic indicators. The tax accounting equation, a fundamental principle in financial accounting, offers a unique lens through which to examine potential discrepancies that might signal the presence of such concealed economic activity. While primarily designed to ensure the financial health and accuracy of individual businesses, the core logic underpinning this equation—the balance between a company’s assets and its liabilities plus equity—can be adapted to identify anomalies that warrant closer scrutiny in the context of tax compliance and the broader underground economy. This report will delve into the definition and components of the tax accounting equation, explore the nature of the underground economy and its relationship with tax non-compliance, analyze how the accounting equation can be used to detect potential hidden economic activity, discuss the limitations of this approach, review existing examples and alternative methodologies for estimating the size of the underground economy, and finally, consider the academic perspectives on the interplay between tax accounting, compliance, and this elusive economic realm.

2. Defining the Tax Accounting Equation and Its Components

At its core, the accounting equation, also known as the basic accounting equation or the balance sheet equation, establishes that a company’s total assets are equivalent to the sum of its liabilities and its owner’s or shareholders’ equity. This foundational principle underpins the double-entry accounting system, ensuring that for every debit recorded, there is a corresponding credit, thus maintaining the balance of the financial records. The equation can be expressed as: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Assets represent the valuable resources that a company owns or controls with the expectation that they will provide future economic benefits . These can include tangible items like cash, inventory, property, and equipment, as well as intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and goodwill. Liabilities, on the other hand, are the obligations or debts that a company owes to external parties, such as loans, accounts payable, and taxes payable. They represent claims against a company’s assets by creditors. Equity, also referred to as owner’s equity or shareholders’ equity, represents the residual interest in the company’s assets after deducting its liabilities. It signifies the owners’ stake in the business and is influenced by factors like invested capital and retained earnings. The accounting equation essentially illustrates how a company’s assets are financed, either through debt (liabilities) or through the investment of owners (equity).

The basic accounting equation can be further expanded to provide a more detailed view of how a company’s operations impact its equity. The expanded accounting equation incorporates revenues, expenses, and owner transactions, often expressed as: Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Capital + (Revenues – Expenses – Withdrawals/Dividends). In this expanded form, Revenues represent the income generated from the company’s primary operations, increasing owner’s equity. Expenses are the costs incurred to generate these revenues, thus reducing equity. Withdrawals by owners in sole proprietorships or partnerships, and Dividends paid to shareholders in corporations, also decrease equity as they represent a distribution of earnings. Retained earnings, a component of equity, accumulate over time as a result of net income (revenues exceeding expenses) that is not distributed to owners.

In the context of tax accounting, taxes payable are recognized as a liability within the accounting equation. However, the underground economy thrives on the non-reporting or underreporting of income and the potential overstatement of expenses, which directly distorts the true representation of a business’s assets, liabilities, and particularly its equity. By understanding the fundamental balance and the typical relationships between these components, analysts can begin to identify unusual patterns or significant deviations that might indicate a disconnect from legitimate economic activity.

3. Understanding the Underground Economy and Its Connection to Tax Non-Compliance

The underground economy, also known by various names such as the shadow economy, black market, or informal economy, encompasses economic transactions that are hidden from official view and therefore escape government regulation and taxation. This hidden realm includes both legal activities that are deliberately unreported to avoid taxes or regulations, and illegal activities involving the production and trade of unlawful goods and services.

A primary driver behind the existence and growth of the underground economy is the desire to avoid tax obligations. This manifests in two main forms: tax avoidance and tax evasion. Tax avoidance refers to the legal strategies employed by individuals and businesses to minimize their tax liability, often by taking advantage of deductions, credits, and other allowances within the existing tax laws. While legal, aggressive tax avoidance can sometimes blur the lines with tax evasion. Tax evasion, on the other hand, involves the illegal act of intentionally underpaying or failing to pay taxes owed to the government. This can include activities such as underreporting income, overstating deductions, concealing assets, or simply not filing tax returns. Both tax avoidance and, particularly, tax evasion contribute significantly to the underground economy by reducing the amount of income reported to tax authorities and, consequently, the tax revenue collected by governments.

Individuals and businesses participate in the underground economy for a multitude of reasons, with tax avoidance and evasion being prominent among them. High tax rates and complex tax systems can create a strong incentive for individuals and businesses to operate off the books. Additionally, the desire to avoid government regulations, labor laws, and administrative burdens can push economic activity into the hidden sector. For some individuals, particularly those facing unemployment or lacking opportunities in the formal economy, the underground economy may provide a necessary source of income. Employers might also be motivated to participate to avoid payroll taxes, licensing fees, and labor union involvement.

The consequences of a large underground economy are far-reaching. Governments suffer from significant losses in tax revenue, which can hinder their ability to fund public services and infrastructure. Law-abiding businesses face unfair competition from those operating in the underground economy who can offer lower prices by evading taxes and regulations. Workers in the informal sector often lack the legal protections and benefits afforded to those in the formal economy, and consumers may be at risk when dealing with unregistered businesses. While some argue that the underground economy can provide a safety net and stimulate economic activity by providing income to marginalized individuals, the overwhelming consensus points to its detrimental effects on fair and efficient economic systems. Accurately measuring the size and scope of the underground economy remains a significant challenge due to its very nature of being hidden from official view.

4. The Tax Accounting Equation as a Tool for Detection: Identifying Discrepancies and Anomalies

The fundamental principle of the accounting equation, which dictates that assets must always equal the sum of liabilities and equity, provides a powerful framework for identifying potential discrepancies or anomalies in reported financial data that could indicate the presence of unreported income or activities associated with the underground economy. Because the equation must always balance, consistent deviations from expected financial relationships within a company or when compared to industry norms can act as red flags, suggesting that some financial activities may be occurring outside the purview of formal reporting.

Several specific types of discrepancies in the accounting equation can raise suspicion. An unexplained or disproportionate increase in a company’s assets, particularly liquid assets like cash, without a corresponding increase in reported income or equity, could suggest that the business is generating unreported revenue that is not being fully accounted for. Conversely, unusually low reported liabilities, while potentially indicating strong financial health, could also be a sign that a business operating in the underground economy is avoiding formal borrowing or conducting transactions primarily in cash, thus minimizing its recorded obligations. An exceptionally high equity balance relative to the scale of the business’s operations and its reported income might also be an anomaly. While a healthy equity position is generally desirable, an unusually high balance could indicate that the owners are not reporting all withdrawals or are disguising personal expenses as business costs within the hidden economy.

Furthermore, a significant mismatch between an individual’s or business’s reported income and their apparent lifestyle or expenditures, a technique often employed in forensic accounting, can strongly suggest the presence of unreported income. For instance, an individual reporting a modest income but possessing substantial assets or engaging in lavish spending might be deriving income from undisclosed sources within the underground economy. Analyzing cash flow statements can also reveal inconsistencies. High levels of cash sales reported by a business coupled with an unusually low reported net income could indicate that a portion of the cash inflows is not being properly accounted for. Difficulties or inconsistencies encountered when attempting to reconcile reported income with bank statements or other corroborating financial records can also serve as a significant red flag.

Forensic accounting itself is a specialized field that integrates accounting, auditing, and investigative skills to examine financial records for evidence of fraud, financial crimes, or other irregularities, including tax evasion. Forensic accountants utilize a range of techniques, such as net worth analysis, which involves comparing an individual’s or entity’s assets minus liabilities over time to identify unexplained increases in wealth that cannot be attributed to reported income. Asset tracing techniques are used to follow the flow of funds and identify hidden assets that may not appear on formal financial statements. Analyzing transaction patterns and identifying unusual or suspicious financial activities are also key components of forensic investigations aimed at uncovering tax evasion and the hidden economy. The underlying principle in many of these forensic approaches is to look for imbalances or illogical relationships within the framework of the accounting equation and related financial statements.

5. Limitations of Relying Solely on the Tax Accounting Equation

While the tax accounting equation offers valuable insights into potential discrepancies indicative of the underground economy, it is crucial to acknowledge its limitations as a sole detection method. The very nature of hidden transactions and the sophistication of concealment techniques can often obscure the true picture, even when analyzing financial records.

A significant portion of the underground economy operates through cash-based transactions, which, by their nature, are difficult to trace through formal accounting systems. These transactions may leave minimal or no direct record in the traditional balance sheet or income statement. Furthermore, a segment of the underground economy involves barter and informal exchanges of goods and services, which may not be recorded in monetary terms at all, thus bypassing the accounting equation altogether.

Individuals and corporations engaged in large-scale tax evasion may employ sophisticated evasion techniques involving complex legal and financial structures, such as shell companies and offshore accounts, making simple balance sheet analysis insufficient to detect their activities. Moreover, those seeking to conceal income or evade taxes may intentionally falsify accounting records, making it challenging to rely solely on these documents for accurate detection. They might maintain multiple sets of books or deliberately alter financial entries to misrepresent their financial position.

The accounting equation operates under the monetary unit assumption, which assumes that all monetary units have the same value over time. However, inflation can distort the comparability of financial statements across different periods, and non-monetary transactions may not be accurately reflected. In some instances, the financial data required for a comprehensive analysis might lack transparency and disclosure, particularly in privately held businesses or within illicit operations, hindering the ability to fully utilize the accounting equation for detection.

The balance sheet, which is directly linked to the accounting equation, provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. Underground economic activities can be transient or fluctuate significantly, and a single balance sheet might not capture the full extent of hidden transactions occurring over a longer period. Therefore, while the accounting equation provides a critical foundation for financial analysis, its effectiveness as the exclusive tool for uncovering the intricacies of the underground economy is inherently limited by these factors.

6. Case Studies and Examples of Accounting-Based Analysis

While the direct application of the accounting equation to macroeconomically quantify the entire underground economy is challenging, accounting principles and forensic techniques play a vital role in identifying tax evasion, a significant component of this hidden sector. Tax authorities, such as the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in the United States, routinely employ forensic accountants to scrutinize financial data, analyze bank records, and compare reported income with individuals’ lifestyles to uncover potential unreported earnings. For instance, forensic accounting methods are often used to investigate cash-intensive businesses, where the potential for underreporting cash receipts is high. Techniques like net worth analysis, which compares changes in an individual’s assets and liabilities over time with their reported income, can reveal discrepancies suggesting hidden income sources.

Government reports on the tax gap, which represent the difference between the total amount of taxes owed and the amount actually paid, often rely heavily on the analysis of accounting data and audit results. These analyses involve comparing reported income and deductions to established benchmarks and investigating anomalies identified through audits. For example, the IRS regularly publishes estimates of the tax gap, highlighting areas of non-compliance such as the underreporting of business income. Similarly, state revenue departments often conduct studies and publish reports on the underground economy within their jurisdictions, utilizing accounting data from audits and other sources to estimate the scale of unreported activity and lost tax revenue. These reports often benchmark the size of the underground economy and identify specific industries or sectors where non-compliance is prevalent.

While academic studies directly linking the accounting equation to macroeconomic estimates of the underground economy are somewhat limited in the provided material, the principles of accounting are fundamental to various estimation methods. For example, the analysis of expenditure-income discrepancies in national accounts, an alternative method discussed later, implicitly relies on the accounting identity at the macroeconomic level. Furthermore, academic research in forensic accounting explores the application of accounting principles and investigative techniques to detect financial fraud and tax evasion at the individual and business levels.

| Country/Region | Method Used | Key Findings | Data Source |

| United States | IRS Tax Gap Analysis | Significant underreporting of business income contributes to the tax gap. | IRS Reports |

| Washington State | Underground Economy Reports | Uncovered unregistered businesses and assessed significant unpaid taxes. | Washington State Department of Labor & Industries |

| Ghana | Currency Demand Approach | Tax evasion averaged 20.78% of GDP. | Academic Study |

7. Alternative Methodologies for Estimating the Underground Economy

Given the limitations of solely relying on the tax accounting equation, economists and researchers have developed various alternative methodologies to estimate the size and scope of the underground economy. These methods often operate at a macroeconomic level and utilize indirect indicators to infer the extent of hidden economic activity.

The Currency Demand Approach (CDA) is a widely used method that posits a positive correlation between the size of the underground economy and the demand for currency. The underlying theory is that transactions within the hidden economy are more likely to be conducted using cash to avoid leaving a paper trail and detection by authorities. By analyzing the demand for currency in relation to factors like the tax burden and interest rates, economists attempt to isolate the portion of currency demand that is attributable to underground activities. While relatively easy to apply, the CDA relies on strong assumptions, such as all underground transactions being conducted in cash and a stable relationship between currency demand and the tax burden, which may not always hold true.

Another approach involves analyzing the discrepancy between national expenditure and income statistics. In theory, the total income generated within an economy should equal the total expenditure. A significant difference between these two measures can be interpreted as an indicator of unreported income and, consequently, the size of the underground economy. This method utilizes readily available macroeconomic data but assumes that all expenditure and income measures are constructed without error and that the discrepancy solely reflects hidden economic activity, which may not be the case.

The MIMIC (Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes) Model is a more sophisticated econometric approach that treats the underground economy as an unobservable or latent variable. This model uses statistical techniques to simultaneously analyze the relationships between several observable “causes” that are believed to influence the underground economy (such as the tax burden, level of regulation, and unemployment rate) and several observable “indicators” that are thought to reflect its size (like currency in circulation, labor force participation rates, and electricity consumption). While capable of considering multiple factors, the results of MIMIC models can be sensitive to the selection of variables and the underlying assumptions of the model.

The Physical Input Method, such as analyzing electricity consumption, operates on the assumption that overall economic activity, both formal and informal, is correlated with the consumption of certain physical inputs. By comparing the growth in electricity consumption with the growth in official GDP, the difference is sometimes attributed to the growth of the underground economy. However, this method also has limitations, as not all underground activities are energy-intensive, and energy efficiency can change over time.

In comparison to the accounting equation approach, which primarily focuses on the financial records of individual businesses, these alternative methods generally aim to provide macroeconomic estimates of the entire underground economy using indirect indicators. While the accounting equation relies on reported financial data, which is precisely what the underground economy seeks to avoid, these alternative methods attempt to infer the scale of hidden activity through broader economic trends. Forensic accounting, which utilizes accounting principles, can be effective in detecting individual cases of tax evasion, but scaling this to estimate the entire underground economy presents significant challenges.

8. Challenges and Complexities in Accurately Measuring the Underground Economy

Accurately measuring the underground economy, regardless of the method employed, is an inherently complex undertaking due to the fundamental nature of the activities involved. By its very definition, the underground economy consists of activities that are hidden from official view, making direct observation and measurement virtually impossible.

The lack of a standardized definition of the underground economy further complicates measurement efforts. Different studies and methodologies may include or exclude various types of activities, leading to inconsistencies in estimates and making cross-country comparisons difficult. Many estimation methods rely on macroeconomic data that may not perfectly capture the nuances of underground activities and can be subject to their own statistical errors and limitations.

Indirect methods, such as the currency demand approach and MIMIC models, depend on various assumptions about the behavior of economic agents and the relationships between observable indicators and the unobservable underground economy. These assumptions may not always hold true in reality, and the results can be highly sensitive to the specific model specification and the choice of variables. Direct methods, such as surveys and tax audits, face challenges related to ethical and legal considerations, as individuals and businesses may be reluctant to truthfully disclose their involvement in unreported activities.

Furthermore, the dynamic nature of the underground economy, which can rapidly adapt to changes in economic conditions, government policies, and technological advancements, makes it a constantly moving target for measurement. The rise of digital payment systems and online platforms, for instance, presents new challenges for traditional measurement techniques that often focus on cash transactions. These complexities underscore the difficulty in obtaining a precise and universally accepted measure of the underground economy through any single method.

9. Academic Perspectives: Tax Accounting, Tax Compliance, and the Underground Economy

Academic research offers valuable insights into the intricate relationships between tax accounting practices, levels of tax compliance, and the prevalence of the underground economy. A recurring theme in the literature is the significant impact of the tax burden on the size of the underground economy. Studies consistently show a positive correlation between higher tax rates and a larger hidden sector, as individuals and businesses seek to avoid increased tax obligations by operating off the books. The complexity of the tax system itself can also contribute to non-compliance and participation in the underground economy.

Similarly, the level of regulation within the formal economy, particularly in labor markets, is often cited as a driver of underground economic activity. Increased regulatory burdens can raise labor costs and reduce flexibility for businesses, incentivizing them to operate informally to circumvent these requirements.

Tax compliance behavior is another critical factor explored in academic research. Elements such as tax morale (the intrinsic willingness to pay taxes), the perceived fairness and efficiency of the tax system, and the perceived risk of detection and penalties for tax evasion all play a significant role in shaping individuals’ and businesses’ decisions regarding tax compliance and their potential involvement in the underground economy.

Academic studies also extensively analyze the macroeconomic consequences of a substantial underground economy. These consequences include reduced government tax revenues, which can limit public spending on essential services; distorted official economic indicators, making it difficult for policymakers to make informed decisions; and potential negative impacts on overall economic growth and investment.

Some research explores the role of financial development in relation to the shadow economy. Improved access to formal financial institutions might reduce the reliance on cash transactions and potentially shrink the underground economy. The increasing prevalence of technology, such as digital platforms and mobile money, presents a more nuanced picture, as these tools can facilitate both formal and informal economic activities, requiring further research to fully understand their impact. Overall, academic perspectives emphasize the complex interplay of economic, regulatory, behavioral, and technological factors that contribute to the existence and size of the underground economy and its close relationship with tax accounting and compliance.

10. Conclusion

The tax accounting equation, while primarily a tool for assessing the financial health of individual businesses, offers a valuable framework for identifying potential discrepancies that may indicate tax evasion and the presence of underground economic activity. The fundamental principle of balance within the equation, along with forensic accounting techniques that scrutinize financial records for anomalies, can help uncover unreported income and concealed assets. However, relying solely on the accounting equation to fully uncover the underground economy has inherent limitations due to the prevalence of cash-based transactions, barter, sophisticated evasion methods, and the potential for intentional falsification of records.

Alternative methodologies, such as the currency demand approach, expenditure-income discrepancies, and the MIMIC model, attempt to estimate the macroeconomic size of the underground economy using indirect indicators. Each of these methods comes with its own set of assumptions and limitations, highlighting the significant challenges involved in accurately measuring this hidden sector. Academic research consistently underscores the strong relationship between tax burdens, regulation, tax compliance behavior, and the size of the underground economy, emphasizing the complex interplay of various economic and social factors.

In conclusion, while the tax accounting equation can serve as a useful tool in the detection of potential tax non-compliance at the micro-level, a comprehensive understanding and measurement of the underground economy requires a multi-faceted approach. This approach should integrate accounting analysis, the use of macroeconomic indicators, robust tax enforcement mechanisms, and broader policy initiatives aimed at promoting tax compliance and reducing the incentives for individuals and businesses to operate within the shadows. Addressing the challenges posed by the underground economy is crucial for maintaining fair and efficient tax systems and ensuring overall well being.

Reporter: Marshanda Gita – Pertapsi Muda

Share

Berita Lainnya

The Accounting Equation and its Implications for Tax Analysis

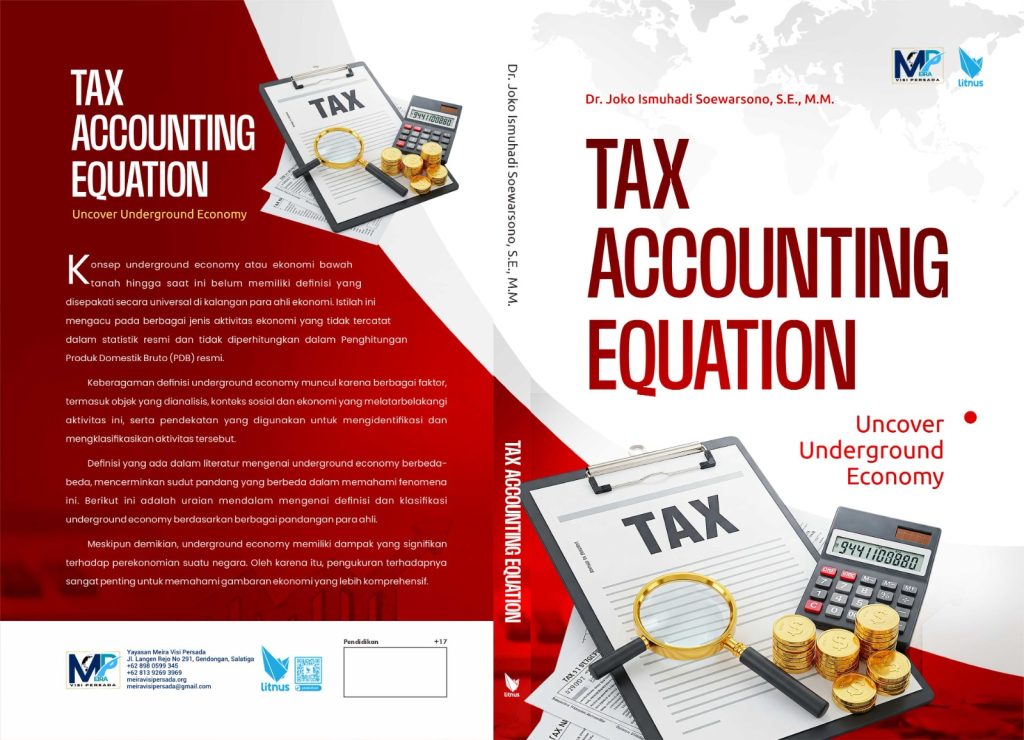

Corporate Financial Crime in Indonesia: An Analysis of Dr. Joko Ismuhadi Soewarsono’s Recent Work

2 Hari Lagi Webinar Langkah Mudah Lebih Produktif di Bulan Ramadhan dengan Mindfulness akan dimulai!

Persamaan Akuntansi Pajak: Alat Forensik untuk Mendeteksi Aktivitas Ekonomi Bawah Tanah dan Penghindaran Pajak

Probowo dan Gibran Resmi Jadi Presiden-Wapres RI 2024-2029

Program Diploma 3 Perpajakan Usakti Wisuda Mahasiswa di JCC Jakarta

Rekomendasi untuk Anda

Berita Terbaru

Eksplor lebih dalam berita dan program khas fiskusnews.com

Tag Terpopuler

# #TAE

# #TAX ACCOUNTING EQUATION

# #TAX FRAUD

# #TAX EVASION